The Grandstand has been a great venue to host a rodeo, and over the years it has hosted many, with aspiring bull riders testing their mettle for Yorkton audiences. But what was it like for those cowboys? In 1983, at the 100th Yorkton Fair, Yorkton This Week’s Jeff Rud spoke to two bull riders about their experience. The following is his story, reprinted from the July 13, 1983 edition.

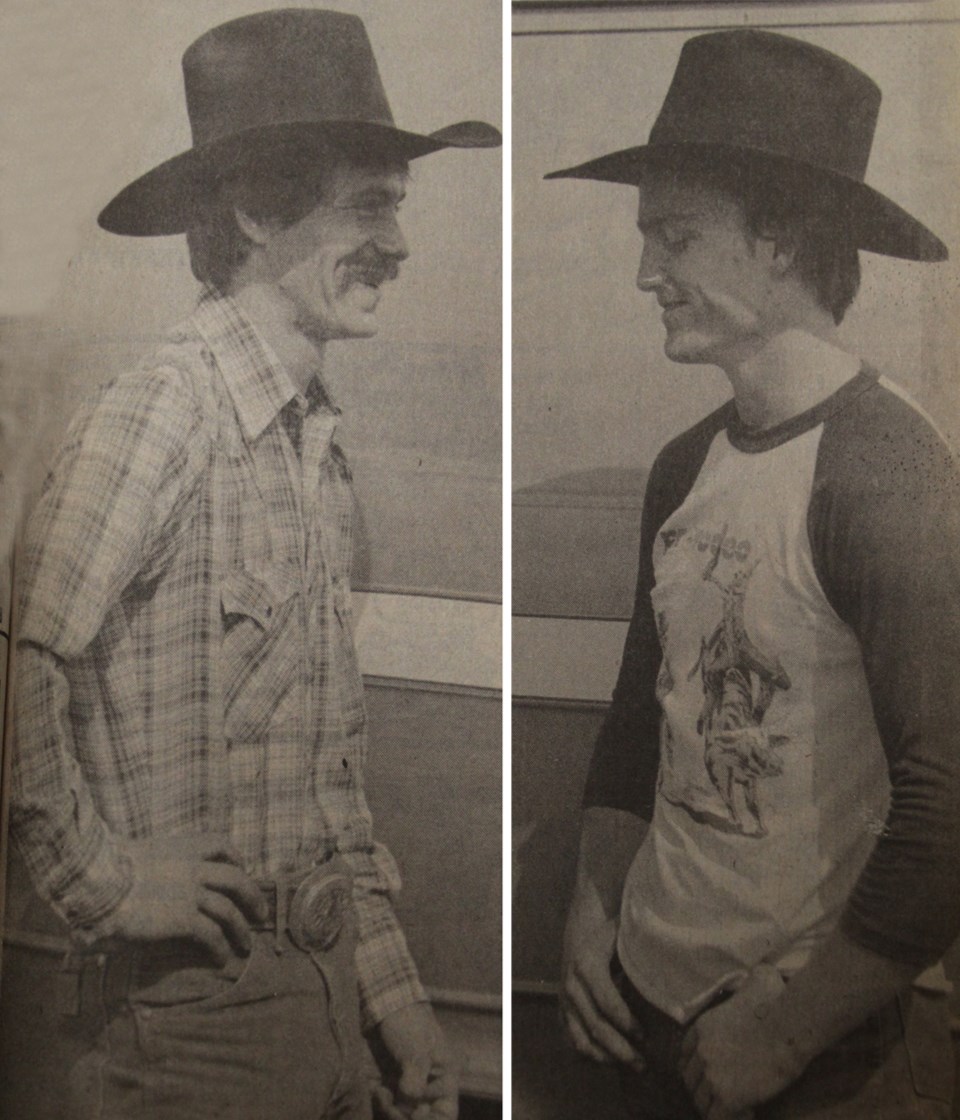

Cody Snyder and Dan Lowry relaxed with a beer in the shade of their van last Wednesday afternoon, gearing up for another long series of trips.

The pair had just finished competing in the bull riding event, part of last week’s Saskatchewan Stampede and Exhibition rodeo.

There wasn’t much time to reflect on their performances, however. They had to hit the road for Alberta and the prestigious Calgary Stampede bull riding event Friday. By Sunday, they were in Montana for another rodeo.

“The bull didn’t buck,” drawled Snyder, summing up his ride in Yorkton, one of the few events he hasn’t placed in this year.

“That’s half the marking – the way the bull bucks. It’s really the luck of the draw.”

The other half of evaluation in bull riding is, of course, how well the cowboy rides. Snyder and Lowry have excelled in that respect so far this year.

Snyder, at just 20 years of age, is second in the Professional Rodeo Cowboys’ Association world bull riding standings this season while his travelling partner, Lowry, is fourth.

After a couple of lean yeas as a pro, Snyder has come into his own as one of the top circuit bull riders. This year alone he has made $38,000 ($89,836 in 2020 dollars).

Lowry, 29 and a seven-year professional, is no slouch either. He has pocketed $28,000 ($66,195 in 2020 dollars) this season.

“This year we’ve both set our goals on making the national finals,” says Snyder, referring to the ultimate in rodeo competitions, held in Oklahoma City each December.

The top 15 riders qualify for the event which is televised across North America and offers huge amounts of prize money.

“It’s like the Super Bowl or World Series of rodeo,” says Lowry. “This year, we’ll both be there.”

Despite their optimism, success hasn’t come easy or without sacrifices for Lowry and Snyder. Snyder of Medicine Hat quit school in Grade 11 while Lowry of Valleyview, Alta. toiled several years as a pro before making any big money.

“It was either go to school and stay amateur or get my pro card and go to work,” says Snyder, who hasn’t looked back since.

Both men grew up on ranches around relatives and friends who made the rodeo their lives. It has definitely influenced them.

“From the first time I ever saw a rodeo, that’s all I’ve ever wanted to do,” says Snyder.

Part of making big money on the pro circuit is travelling thousands of miles from rodeo to rodeo. Snyder, Lowry and a collection of other cowboys travel together, often as many as 10 of them squeezing into one van.

They compete in rodeos all the way from Texas to Yorkton, trying to hit the biggest ones and those which offer the most prize money.

Deciding which rodeos to attend isn’t always easy, as there are more than 700 sanctioned events in North America each year.

Top Canadian rodeos offer up to $1,500 in prize money ($3,500 in 2020 dollars) for bull riding while some of the bigger U.S. competitions feature as much as $4,000 ($9,500 in 2020 dollars) per event.

One of the drawbacks of the rodeo circuit is that it goes virtually year-round. Snyder and Lowry don’t, as a rule, get much of a holiday.

Bull riders risk injury every day as their event is considered by some to be the most dangerous in the rodeo.

Lowry and Snyder don’t consider it hazardous work, however. When asked if he’s ever been seriously hurt, Snyder almost forgets to mention that last year he was stepped on by a bull, resulting in two broken limbs and a punctured lung.

“You’re going to get hurt no matter what event you’re in,” explains Lowry.

So why would anyone want to get up on a mean, ornery bull only to be thrown off eventually?

“It was the only event I was good at and I enjoyed it more than the rest,” says Lowry.

Bulls used for competition are bred to buck. They are raised to be mean and, in most cases, they don’t disappoint.

The only way to learn how to ride these animals is to get up on them time and time again. Technique is mastered the hard way.

“You’ve got to really want to do it,” says Lowry.

“Generally, it’s a younger man’s sport, for guys between 22 and 30,” says Snyder, eyeing his older partner with a grin.

“There are some exceptions though,” he quickly adds.

Although both riders hail from Alberta, they speak more like Texans, the drawl coming as part of the trade.

“I don’t even notice it,” says Snyder.

“That’s all we’ve been is across the line (border) for the past six months.”